Architecture of Malla Period Palaces and Basic Houses

The residences of kings during the Malla period were more elaborate than those of wealthy citizens, featuring greater space and quadrangles. The architecture displayed intricate woodwork, with double columns and brackets. Floor joists were extended beyond the walls, adorned with elaborate decorative tiles and carvings.

Sajhyas, or large windows, were expanded to create continuous galleries, projected by short brackets. Carved, nonfunctional panels often flanked doors, which were crowned with toranas (ornamental archways). The facing bricks had a deep red, lustrous glazed finish, and tiles were used as protective cornices.

Read Also : Malla Architecture of Nepal: A Historical and Urban Perspective

The ground floors served multiple purposes, including guard rooms, reception areas (phalacha), and functions for the royal office. A separate royal chapel, known as agamchem, was present within the complex, along with various temples scattered throughout the palace grounds. The treasury was located in an adjoining garden referred to as the Bhandarkhal. Unlike in typical homes, palaces did not feature cat-windows, indicating that dining areas were situated elsewhere.

Expansion of the palace was achieved by adding quadrangles rather than traditional wings. Bhaktapur once had a remarkable 99 quadrangles, Kathmandu had 55, while Patan boasted fewer than a dozen (Slusser, 1982). These palatial structures also served defensive purposes and were collectively referred to as kvachem. The Tripura palace was specifically known as kvachem, while the Patan palace was termed chaukota, meaning “four-cornered fort,” due to a fortified structure at its northern end.

Palaces were equipped with pleasure pavilions, ponds, fountains, baths, and gardens. Despite their larger scale and richer embellishments, these palaces maintained harmony with their surrounding architecture, unlike the grand European palaces or the more ostentatious durbars of the Ranas. The lack of specific orientation and informal addition of quadrangles meant that these structures did not require the wide axes and extensive gardens typical of Indian and Western palaces.

Following the conquest of Prithvi Narayan Shah, Kathmandu became the capital, leading to the cessation of the royal residences in Patan and Bhaktapur, which instead became government departments. After 1885, the royal family relocated to the Narayan Hiti Durbar, previously owned by Jung Bahadur’s brother, Rana Uddip Singh. The Hanuman Dhoka palace subsequently became a venue for royal ceremonies, including coronations, marriages, and festivals.

Read Also : Urban Conservation of Nagadesh, Madhyapur Thimi Municipality, Bhaktapur, Nepal

Kathmandu Durbar Square

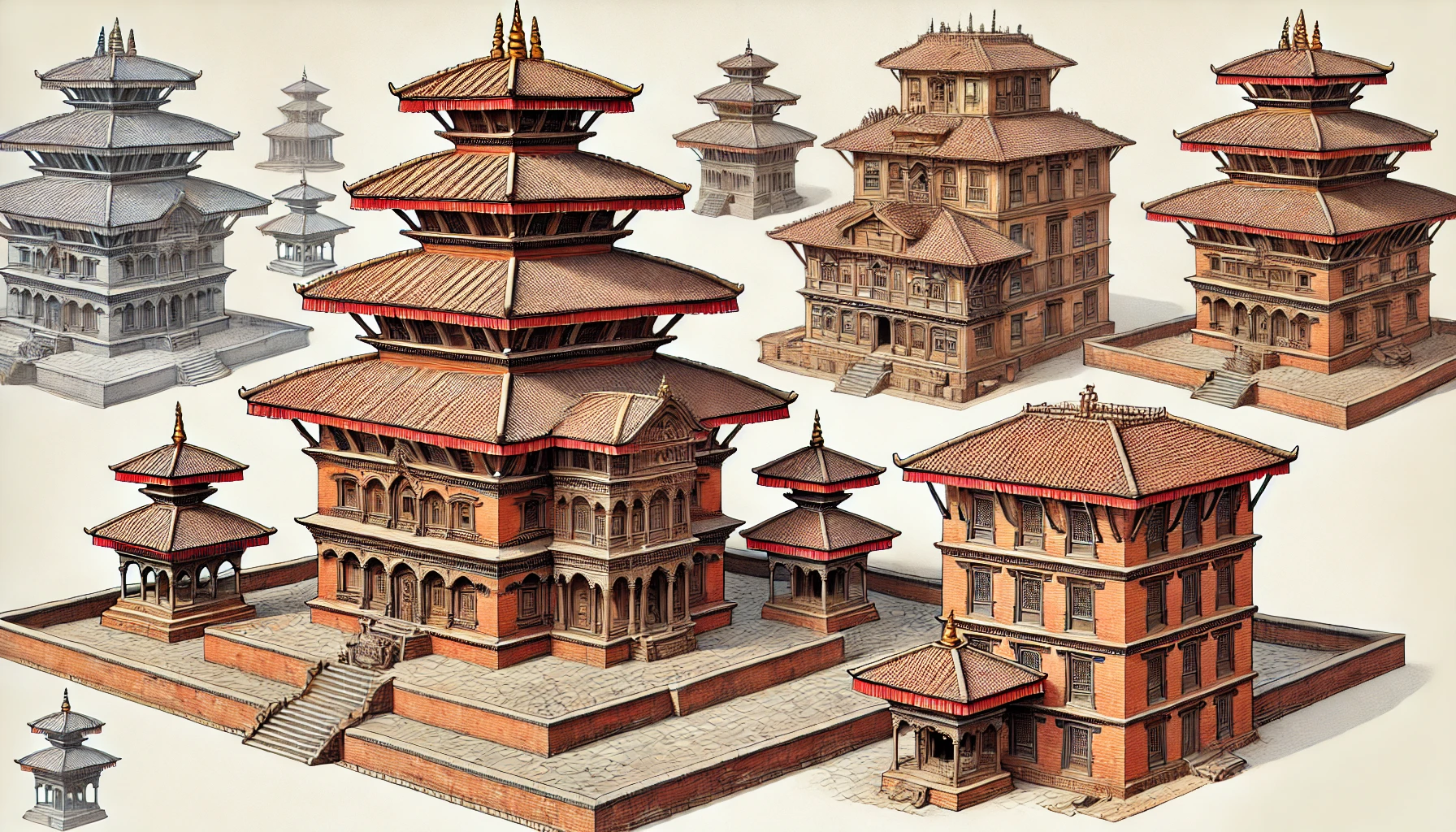

Kathmandu Durbar Square, also known as Hanuman Dhoka, is a historical palace complex located in the heart of Kathmandu. Established by Gunakamadeva in the 10th century, it has undergone significant expansions over the centuries. The complex derives its name from the statue of Hanuman at its main entrance and has served as a royal residence for both Malla and Shah kings.

Originally comprising 35 courtyards (chowks), only nine remain today due to renovations and the impact of natural disasters over time. Among its notable features is the Taleju Temple, constructed in 1564 by Mahendra Malla. This temple, standing at 37 meters tall, is recognized as one of the most richly adorned temples in the city.

Pratap Malla, a pivotal figure in the development of the palace complex, contributed to its expansion by adding several courtyards, temples, and structures such as Nasal Chowk, Mohan Chowk, and Sundari Chowk. Historically important for religious and cultural activities, the Durbar Square underwent extensive modifications during the 20th century, including the creation of New Road and the construction of Gaddi Baithak in a neoclassical style. Today, the square remains a focal point for cultural heritage, reflecting the architectural grandeur and urban evolution of Kathmandu.

Read Also : Bhaktapur Durbar Square: A Study in Architectural and Urban Planning Fabric

Patan Durbar Square

Caukot Durbar, commonly referred to as Patan Palace, is a historically significant royal complex situated in the heart of Patan, adjacent to a large temple-filled square. Unlike the palaces of Kathmandu and Bhaktapur, Patan Palace has successfully preserved its traditional Malla-period architecture, characterized by brick walls, intricately carved woodwork, and tiered roofs. The palace features four quadrangles and has maintained its original design due to minimal remodeling over the years.

Patan, initially a Lichchavi settlement called Yupagrama, was later annexed by Sivasimhamalla in 1597, highlighting the influence of the Malla era. Significant structures within the palace, such as the Degutale temple and Sundari Chowk, were constructed by Siddhinarsimha in the 17th century, expanding the palace southward. His son, Srinivasa, continued this legacy by restoring existing structures and building new ones, including the Bhimsena temple and Mulchowk.

Sundari Chowk, which served as the main living quarters for the king, is notable for its exquisite stone carvings, a gilded water fountain (Tusa Hiti), and bathing taps, which later inspired similar features in Kathmandu’s palaces. The quadrangles within the palace complex are largely self-contained with minimal interconnection, reflecting the influence of traditional viharas (monastic courtyards) on its layout and function.

Read Also : Patan Durbar Square : Prospects of Majestic Heritage

Baktapur Durbar Square

Tripura Layku, known as Bhaktapur Palace, was constructed in the mid-12th century by Anandadeva and underwent several expansions, once comprising up to 99 courtyards. Today, however, only six remain due to the damage caused by the 1934 earthquake. Unlike the palaces in Kathmandu and Patan, Bhaktapur Palace is situated away from major trade routes and lacks the prominent tower temples typically associated with royal complexes.

The palace features significant structures like Mulchowk, believed to date back to the original Tripura layout, and Bhairav Chowk, which was built by Sadashiva Malla in 1580. Key contributions to the palace were made by rulers such as Jitamitramalla, Bhupatindra Malla, and Ranajit Malla. Jitamitramalla extensively renovated Kumari Chowk and added a water spout, while Bhupatindra Malla is credited with restoring courtyards and constructing notable monuments, including the 55-Window Gallery and the Nyatapola temple.

Ranajit Malla gilded the palace’s main gate, Sun Dhoka (Golden Gate), in 1754 as an offering to the goddess Taleju. The unique layout of the Bhaktapur Palace, distinct from other palaces in the Kathmandu Valley, features clusters of temples surrounding the palace, although many of these were destroyed in earthquakes.

Read Also : Kathmandu Durbar (Hanumandhoka): A Historical Journey from Malla Period

Malla Period Basic Houses

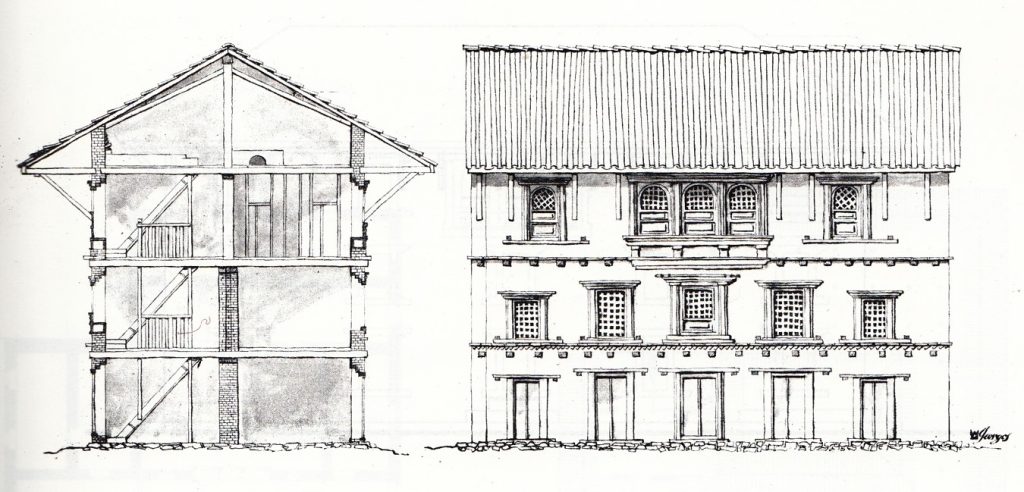

Malla period architecture, particularly in Newar houses, is characterized by narrow, rectangular, brick-walled structures typically three stories high, with the topmost floor serving various purposes. These buildings were joined end-to-end around a communal courtyard, which facilitated daily activities and social gatherings. The houses featured shallow foundations, thick brick walls, and minimal openings on the ground floor, which was generally reserved for storage or workshops.

The upper floors showcased intricately carved windows, such as sajhyas, which were large, latticed, and served as the primary decorative elements of the façade. These windows provided light and ventilation, while the top floor typically served as a living or work area, offering larger and brighter rooms.

Low rooftops characterized these homes, constructed with interlocking tiles and a framework of wooden beams, often supported by tunalas (wooden brackets). Roofs typically sloped at 30–40 degrees, with dormer windows occasionally added for additional light.

The design of these houses aimed to separate private from public spaces, with podiums and front steps acting as semi-private buffers. Symmetry was a crucial element, with each floor’s windows arranged independently to maintain a central axis. Water was sourced from both private and public wells, while latrines were kept separate from living spaces due to cleanliness concerns. This compact architectural style reflects the Newar people’s focus on trade, with agriculture being a secondary occupation.

Read Also : URBAN PLANNING HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL KIRTIPUR CITY, NEPAL

Conclusion

The Malla period left a profound impact on the architectural landscape of Nepal, with palaces and residential buildings that embody cultural heritage, artistic expression, and historical significance. The intricate design of Malla period palaces, coupled with the unique characteristics of traditional Newar houses, illustrates the rich architectural tapestry of the Kathmandu Valley.

References

Slusser, M. (1982). Nepalese art and architecture. Brill.

One Comment